Eye disease can’t steal excitement Williams man feels when he jumps

by Barbara Hahn of the Daily Courier

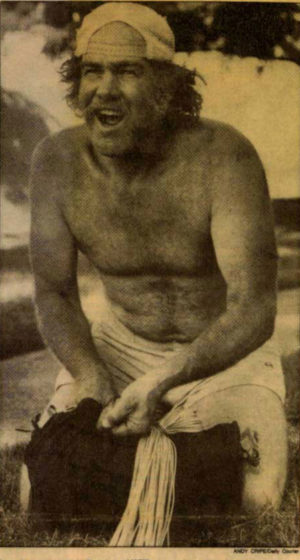

CAVE JUNCTION — Failing through the air at 120 miles per hour, sky diver John Fleming feels as free as a bird.

Unlike a bird, though, Fleming can’t see the ground below. And he can’t see his colorful parachute billowing overhead.

Unlike a bird, though, Fleming can’t see the ground below. And he can’t see his colorful parachute billowing overhead.

Fleming, like his grandfather and a brother, has retinitis pigmentosa, and eye disease that is slowly robbing him of vision. By 1980, his vision had deteriorated to the point he had to give up driving a car. Now he estimates his field of view is at about 15 percent “and getting worse by the day.”

For Fleming, his vision loss doesn’t mean he’s giving up skydiving. Rather, with 1,443 jumps to his name now, his goal is 2,000 jumps.

The 47-year-old Williams resident, afectionately nicknamed “BJ” — short for “Blind John” — by his fellow divers, joined dozens of other divers this weekend at the Illinois Valley Airport for a “boogie.” That’s sky diving lingo for an informal gathering to hone diving skills, practice aerial group configurations and to just plain have a little fun.

It’s not hard to understand his love of the sport.

“You’re completely away from all your worries and troubles,” Fleming says. “I do it because it’s beautiful up there.”

Fleming, formerly a pilot, has been jumping for nearly 30 years. It was back in 1963 when he and some buddies decided on a whim to make their first jump.

“We were watching ‘Wide World of Sports,’ and I said — “I’ve always wanted to do that,” Fleming recalls. “I liked it from the very first jump.”

His experience — and his addiction to the sport — has kept him airborne.

“I’ve jumped so many times that you build a clock in your head to let you know when to open your chute,” Fleming says.

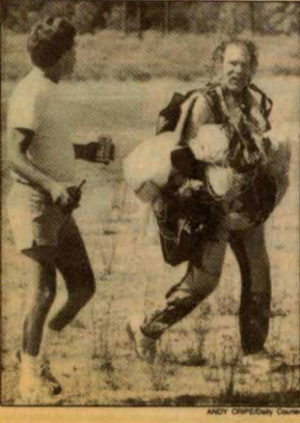

It’s when Fleming gets closer to the ground, though, that he needs some help from friends.

“I’ve got three radios — one on me, one on the ground and one on another sky diver on the jump,” he explains.

Once out of the plane, the sky diver carrying a radio lets him know his relationship to other divers. And as he approaches earth, the land-based radio operator directs him to the landing area and tells him when to pull back on his steering toggles for a controlled landing.

Though there are many blind people who do one or two jumps, Fleming acknowledges there aren’t many who have made sky diving their avocation.

“It’s the free fall, not the parachute ride, for why I sky dive,” he explains.

“To a non-sky diving person, it’s hard to explain why we sky dive,” he said. “I just can’t explain to people about the free fall. It’s just the ride of a lifetime.”

When Fleming and his fellow divers leap from the plane, there’s only a few moments to maneuver into free-fall formation. “That’s really a fun part of it for me, he says. “It’s very technical, and you only have just a little bit of time to make the formation.”

Also, there’s almost an ethereal sense about diving, a time-bending warp that focuses all the senses into the moment.

“Your sense of time is altered,” Fleming says. “You put yourself into slow motion in free fall. A 70-second free fall to me seems like minutes. You’re seeing every minute detail of the fall. You use every second to the fullest.”

Once the chute is open, it’s just a few more minutes before the divers return safely to earth, Fleming said. “The rest is just being together (with other sky divers) and sharing the same interests.”

It’s this camaraderie that makes the sport particularly addicting, he adds.

“There’s people from all walks of life,” he says. They meet up for boogies throughout the Pacific Northwest, practice and perform precision aerial maneuvers, and entertain one another with diving stories way into the night.

“You can’t be goofing around up there,” Fleming says. “One of the reason [sic] we play so hard on the ground is because once we’re in the plane, it’s all business.”

Originally published in Grants Pass Daily Courier, date unknown. Photo credit: Andy Cripe, Daily Courier